British Energy Security Strategy: Homegrown clean power, but at what cost?

Energy transition Energy consultancy Technology

This blog was written in partnership with Flint.

Key takeaways

- The Government’s new ‘British Energy Security Strategy’ is positioned as a direct response to the Russian invasion of Ukraine, arguing that by expanding homegrown power sources, the UK can reduce its exposure to volatile international fossil fuel markets.

- At the heart of the strategy is a new ambition to produce 95% of Great Britain’s electricity from low carbon sources by 2030, supported by more stretching deployment targets for key technologies, including nuclear, wind, solar and hydrogen. This ambition will create significant investment opportunities.

- However, the Government’s target is stretching and will have major consequences. For example our initial analysis suggests that if the Government achieves its goals, then by 2030:

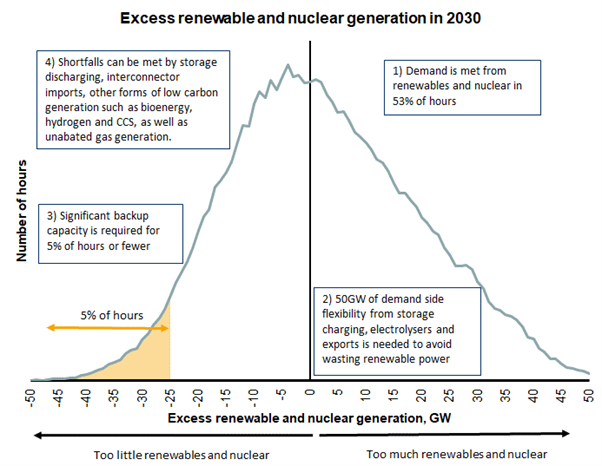

- In more than half the hours of the year there could be excess power from nuclear and renewables, which, to avoid being wasted, would need to be absorbed by exports, energy storage and green hydrogen production;

- In other periods there will be a shortage of renewable generation. Although some of this can be accommodated via storage and demand side response, the system will need a substantial amount of peaking capacity (20-25GW) which is only likely to be called upon for around 5% of the year.

- There is currently little detail on how these key supporting technologies will be delivered, which risks pushing up overall system costs. More detail will be needed on the accompanying policy and regulatory frameworks to ensure greater ambition does not come at a greater price for the consumer.

Summary

The new strategy centres on how the UK can reduce its reliance on international fossil fuel markets, arguing that this will strengthen energy security and cut bills over the next decade. To enable this, the centrepiece of the strategy is an ambition to deliver as much as 95% of Great Britain’s electricity from low carbon sources by 2030 – the previous target was to decarbonise the power system fully by 2035. The strategy includes a range of new targets to accelerate the deployment of key low carbon technologies, alongside renewed support for domestic oil and gas production.

- Nuclear power: The strategy sets an ambition to reach up to 24GW of nuclear power capacity by 2050, serving 25% of electricity demand. To give near-term certainty, the Government has committed to reach a Final Investment Decision on one project in this Parliament, and two in the next. To aid delivery, Government will create a new delivery vehicle – ‘Great British Nuclear’ – to work with international project developers and potential investors.

- Offshore wind: Government wants offshore wind to be the backbone of the UK’s energy mix by the 2030s, setting an ambition to deliver up to 50GW of offshore capacity by 2030, including a new target for up to 5GW of floating offshore wind. This is a very stretching ambition given the current project pipeline. There are much-needed commitments to accelerate consenting timelines, establish a fast-track approval process for certain projects, review the regulatory approval process, and provide projects with strategic compensation to help manage environmental impacts. These are all required to enable the accelerated project development needed to get anywhere near 50GW. Government has also acknowledged the link between increased renewable power capacity, and the need for long-term energy storage solutions, with an ambition to publish a policy framework in 2024 to support investment in long-duration energy storage.

- Hydrogen: the 2030 hydrogen production target has been doubled to 10GW, with electrolysers contributing at least 50% of this. Government aims to run annual allocation rounds supporting green hydrogen production so that 1GW of capacity will be in construction or operational by 2025, at which point it will move to price-based competition. Electrolysers, powered by new renewable capacity, will play an important role in balancing the grid and so deliver wider benefits to consumers beyond the value of the hydrogen itself. Business models are promised to underpin investment in hydrogen transport and storage infrastructure by 2025, which will be critical to enable green hydrogen production to play a role in system management by enabling new hydrogen-powered electricity generation, and providing a means for long-duration energy storage.

- Onshore wind and solar: Political pressure from a range of MPs means that there are no new targets for onshore wind. However, consultation will take place on how projects can progress where there is clear local support. The ambition for solar has increased, with an ambition to grow the current 14GW of solar capacity five-fold by 2035. The focus will be on new solar installations on domestic and commercial rooftops, again, to placate concerns from politicians about the visual impacts of new solar farms.

- Networks and markets: Government has attempted to set a clearer path on delivering the network infrastructure that will underpin these technology targets. There is a marked shift away from a competitive approach to future onshore energy network build, with recognition that certainty and speed in delivery are now key. Government has used the strategy to give Ofgem the steer that it should support anticipatory investment, which is likely to be reflected in the forthcoming Strategy and Policy Statement. There is also a commitment from Government to publish a strategic framework for new network infrastructure this year. The creation of the ‘Future System Operator’, which was also announced last week, will play a pivotal role in the future as it shapes whole-system thinking on the energy system, including strategic infrastructure requirements. There will also be a major review of electricity market arrangements which could have far-reaching implications including for flexibility.

- Domestic oil and gas: The strategy sets out much clearer support for domestic oil and gas production. A new exploration and production licensing round will launch this Autumn, and will follow the finalisation of the new climate compatibility checkpoint to ensure new developments are at least notionally aligned with the net zero target. However, Government has acknowledged that this new activity will do little to cut bills or improve energy security in the short-term due to project timescales. Fracking is addressed, but any future activity will follow a newly announced review of UK shale gas opportunities, with new evidence required to shift the ongoing moratorium on exploration.

Analysis

The new strategy should be viewed as a positive shot in the arm for those with an interest in the UK energy market. In established technology markets – such as fixed offshore wind – the more stretching deployment targets will eventually strengthen the pipeline of available projects. Speed of delivery will be prioritised over competition. This focus on project acceleration should finally help to tackle the various non-technology barriers to deployment.

The strategy certainly brings forward new investment opportunities. After years of indecision, Government has come out firmly in favour of a major expansion of nuclear power. While there are few formal near-term targets, actions on financing and siting give more certainty to a sector where investment has been difficult to secure in the absence of Government, or energy bill payers, shouldering the construction and revenue risks. Despite muted support for new onshore wind, the uptick of ambition on floating wind, long-term energy storage and hydrogen offers industry an opportunity to accelerate the delivery of new projects. Finally, the more vocal support for domestic oil and gas should help reinvigorate investor confidence in the UK North Sea.

But the sheer scale of the challenge of transitioning the energy system to one so heavily dependent on renewables and nuclear has only just begun to be addressed. If the Government’s new 2030 targets for nuclear and renewables are achieved, our initial analysis indicates that there will be an oversupply of power more than half the time (53% of the hours in the year) – up from 6% expected in the coming year.

To keep balancing and constraint costs down, and to mitigate falling revenues for renewable generators, over 50GW of new demand-side flexibility from energy storage, electrolysers and interconnectors will be needed to avoid up to 72TWh of renewable power being wasted (almost three times the yearly output of Hinkley Point C). While the need for flexibility is acknowledged, the strategy includes very little on the demand side of the equation.

Note: Chart shows the amount of time during 2030 in which there will either be too much or too little low-carbon power generation from nuclear and renewables relative to demand. Modelling uses the capacity targets for nuclear, offshore wind, onshore wind, and solar from the British Energy Security Strategy, and wider energy system assumptions from the NG ESO Future Energy Scenarios 2021. Analysis from LCP assumes 50GW offshore wind, 25GW onshore wind, 45GW solar and 4.5GW nuclear in 2030. Peak and total demand are 67.5GW and 330TWh respectively. Historic wind, solar and demand patterns are sampled from 2006-2016 and are updated to align with expected locations and loads factors of the 2030 fleet.

Meanwhile, an additional 45GW of back-up capacity will be needed to fill the gap during periods of low renewable output. This is a clear policy challenge, as nearly half of this capacity could run for as little as 5% of the time. The technologies needed to meet this shortfall are likely to include a mix of low-carbon options, including bioenergy, hydrogen and CCS-enabled power plants, and some unabated gas generation. The current level of ambition in these areas lags behind that for renewables.

The need for significant amounts of flexibility and back-up power show the scale of the new Government ambition to achieve 95% power sector decarbonisation by 2030. Without a concerted programme of policy and regulatory reform to unlock investment on a range of other supporting technologies, there is a risk that the new strategy fails to cut bills in the long-term, and actually puts them up. Attention must now turn to how to deliver homegrown clean power, but in a way that keeps the cost down.

The British Energy Security Strategy can be accessed here.

Authors

Josh Buckland, Partner leads Flint’s work on energy, sustainability and environmental issues. Prior to joining Flint, Josh was Energy Adviser to the Secretary of State for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy.

Flint Director James Diggle advises clients on energy and climate issues, and previously led the energy and climate team at the CBI.

LCP Delta provides energy market expertise and modelling on the GB and Irish electricity markets. LCP Delta provides the UK government with its primary power market forecasting models.