‘Smoke-free generation’ bill could lead to a cohort of young people living up to a decade more in good health – LCP

Health analytics Life sciences

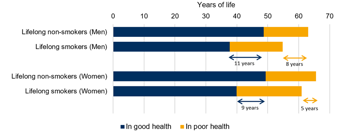

New research from LCP’s Health Analytics team has highlighted that 18-year-olds who never smoke could spend around a decade more of their lives in good health than those who start smoking at 18 and remain lifelong smokers.

Through analysing ONS data and published research, the team have estimated that men are expected to spend, on average, 11 more years in good health (49 vs 38 years), and their remaining life expectancy would be higher by 8 years (63 vs 55 years).

Women are expected to spend, on average, 9 more years in good health (49 vs. 40 years), and their remaining life expectancy would be higher by 5 years (66 vs. 61 years).

Figure 1: Estimated remaining years of life spent in good and poor health for 18-year-old lifelong non-smokers vs smokers

The research comes as the pledge to ban cigarette sales to anyone turning 18 in 2027 and younger, with the aim to create a ‘smoke-free’ generation, is reintroduced at the King’s Speech to deliver on the mission to improve healthy life expectancy. Smoking is a key risk factor for many diseases, and studies have reported a range of reductions in life expectancy. In contrast, its impact on healthy life expectancy is difficult to quantify despite being a novel way of capturing the health impact of smoking that is aligned with the Government’s mission and LCP’s mission to help transition health systems from importers of illness to exporters of health.

Dr Mei Chan, Senior Statistician in LCP’s Health Analytics team, commented: “We welcome the reintroduction of the smoking ban and government efforts to improve healthy life expectancy. This ban would be a promising start as our research shows the impact that smoking from a young age can have on quality of life.

“However, our research on smoking and inequalities in healthy life expectancy shows that alongside this smoking ban, joined-up policy approaches tackling multiple lifestyle factors would strengthen the long-term impact of the smoking ban on the population’s health. This will also help to reduce health inequalities that have been compounded by the pandemic.”

To understand more about our approaches and how this could be applied to other health issues, contact us

Let's talkOur media contacts

Lauren Keith

Head of External Relations

+44 (0) 203 922 1319

Esther Musa

Senior PR Executive

+44 (0) 207 550 4661

Email Esther

Impact of smoking on life expectancy and healthy life expectancy

18-year-olds who remain lifelong non-smokers could spend around a decade more of their lifetime in good health than those who start smoking when they turn 18 and remain lifelong smokers.

Men are expected to spend on average 11 more years in good health (49 vs 38 years) and their remaining life expectancy would be higher by 8 years (63 vs 55 years), while women are expected to spend on average 9 more years in good health (49 vs 40 years) and their remaining life expectancy would be higher by 5 years (66 vs 61 years).

Estimated years of life spent in good and poor health for 18-year-old lifelong smokers vs non-smokers, by sex

| Life expectancy (years) |

Healthy life expectancy (years) | |||||

| Smoker | Non-smoker | Difference | Smoker | Non-smoker | Difference | |

| Men |

54.8 |

63.0 |

8.2 |

37.7 |

48.6 |

10.9 |

| Women |

60.9 |

65.6 |

4.7 |

39.9 |

49.3 |

9.4 |

Context

- The Tobacco and Vapes Bill, where sales of tobacco products to anyone in the UK turning 18 in 2027 and younger will be banned with the aim to create a “smoke-free generation”, has been reintroduced at the King’s Speech. This policy is intended to deliver on the Government’s mission to improve healthy life expectancy and reduce the number of lives lost to the biggest killers, including cancer and cardiovascular diseases.1

- Smoking is a key risk factor for many diseases and studies have reported it is associated with a range of reductions in life expectancy (up to 10 years). In addition, its impact on healthy life expectancy is difficult to quantify.

Methods and data sources

- We have used the Sullivan method to estimate period life expectancy and healthy life expectancy from age- and sex-specific mortality and health prevalences, for current and never smokers. These estimates do not include any forecasts of mortality improvements or changes in health prevalence from current rates.

- We have used age- and sex-specific mortality rates from Office for National Statistics (ONS) for the UK over 2020-2022.2* Rates are only reported to age 100 so we have extrapolated for ages 100-120 assuming a log-linear relationship with respect to age. Smoking status-specific mortality rates are derived from these using average smoking prevalences over 2020-22 from the ONS Annual Population Survey3 and hazard ratios taken from published literature4,5 and smoothed using cubic splines.

- We have combined ONS Annual Population Survey data on overall health prevalence3 (taken as the proportion of individuals who responded they were in “Good” or “Very good” health) in the UK by smoking status, separate ONS data on age-banded sex-specific but non-smoker-status-specific health prevalence, and ONS age- and smoker-status-specific but non-sex-specific health prevalence data.6 We have used a cubic spline to smooth and obtain age- and sex-specific health prevalence rates at single years of age.

- Latest available published mortality rates. Data over this period was impacted by the Covid-19 pandemic. However, using pre-pandemic data (2017-19) would change the differences in life expectancies and healthy life expectancies between lifelong smokers and never-smokers by c. 0.1-0.2 years, indicating that the results are not sensitive to this choice of data source.

References

- The Prime Minister’s Office. The King’s Speech 2024. Last accessed 17 July 2024.

- Office for National Statistics. Mortality rates (qx), by single year of age. Last accessed 20 June 2024.

- Office for National Statistics. Smoking habits in the UK and its constituent countries. Last accessed 20 June 2024.

- Ellis, L, Coleman MP and Rachet B. “The impact of life tables adjusted for smoking on the socio-economic difference in net survival for laryngeal and lung cancer.” British Journal of Cancer (2014): 197.

- Royal College of Physicians. “Hiding in plain sight: Treating tobacco dependency in the NHS.” 2018.

- Mayhew, L, Chan MS and Cairns AJG. “The great health challenge: levelling up the U.K.” The Geneva Papers on Risk and Insurance (2024): 9