Burnt out or something more? Examining the real root cause of NHS workforce challenges

Health analytics

Happy doctors result in happier, healthier patients, as evidenced by the growing body of literature linking higher satisfaction levels among healthcare staff to improved patient satisfaction and care outcomes.

Recognising this, the NHS has several initiatives intended to track and improve staff occupational wellbeing. One initiative is the NHS Staff Survey, launched in 2003 and administered annually across England. In March 2023, the NHS published results from the 2022 Survey against a backdrop of high attrition and widespread workforce shortages. Considering these challenges and the planned Government announcement of a new NHS Workforce Plan, we sought to examine the reasons staff are increasingly dissatisfied.

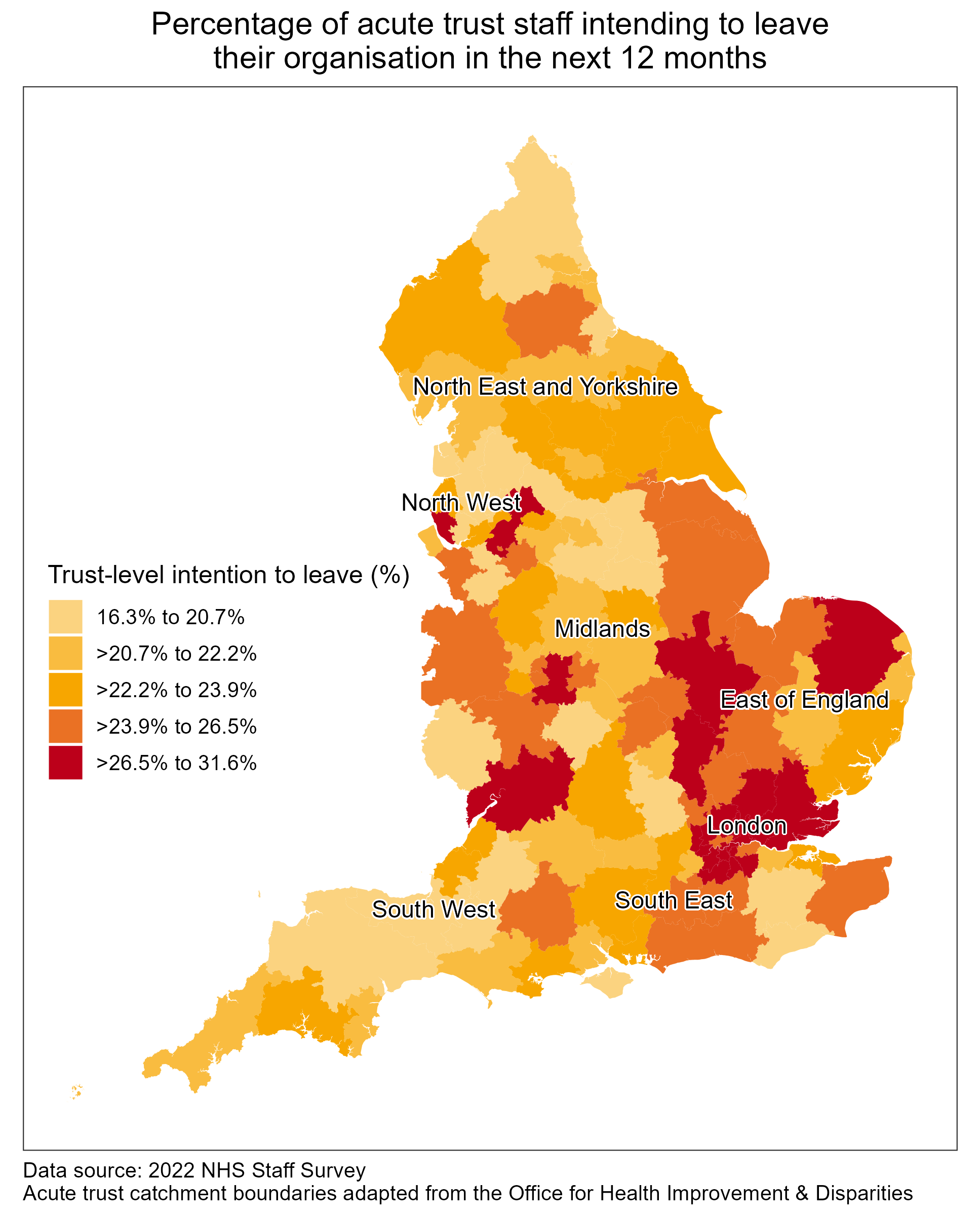

To do this, we looked at results from the 2022 NHS Staff Survey, focusing on acute trusts which represent the majority of trusts in England. Since 2018, the NHS Staff Survey has included a question asking respondents about their intention to look for a job at a new organisation in the next 12 months. This can be used as a proxy measure for overall staff satisfaction. In 2022, 23.8% of acute trust staff across England expressed their intention to leave, up from 23.0% in 2021. That means almost a quarter of NHS staff are considering leaving their organisation in the next year, potentially exacerbating already higher than average vacant posts across hospitals.

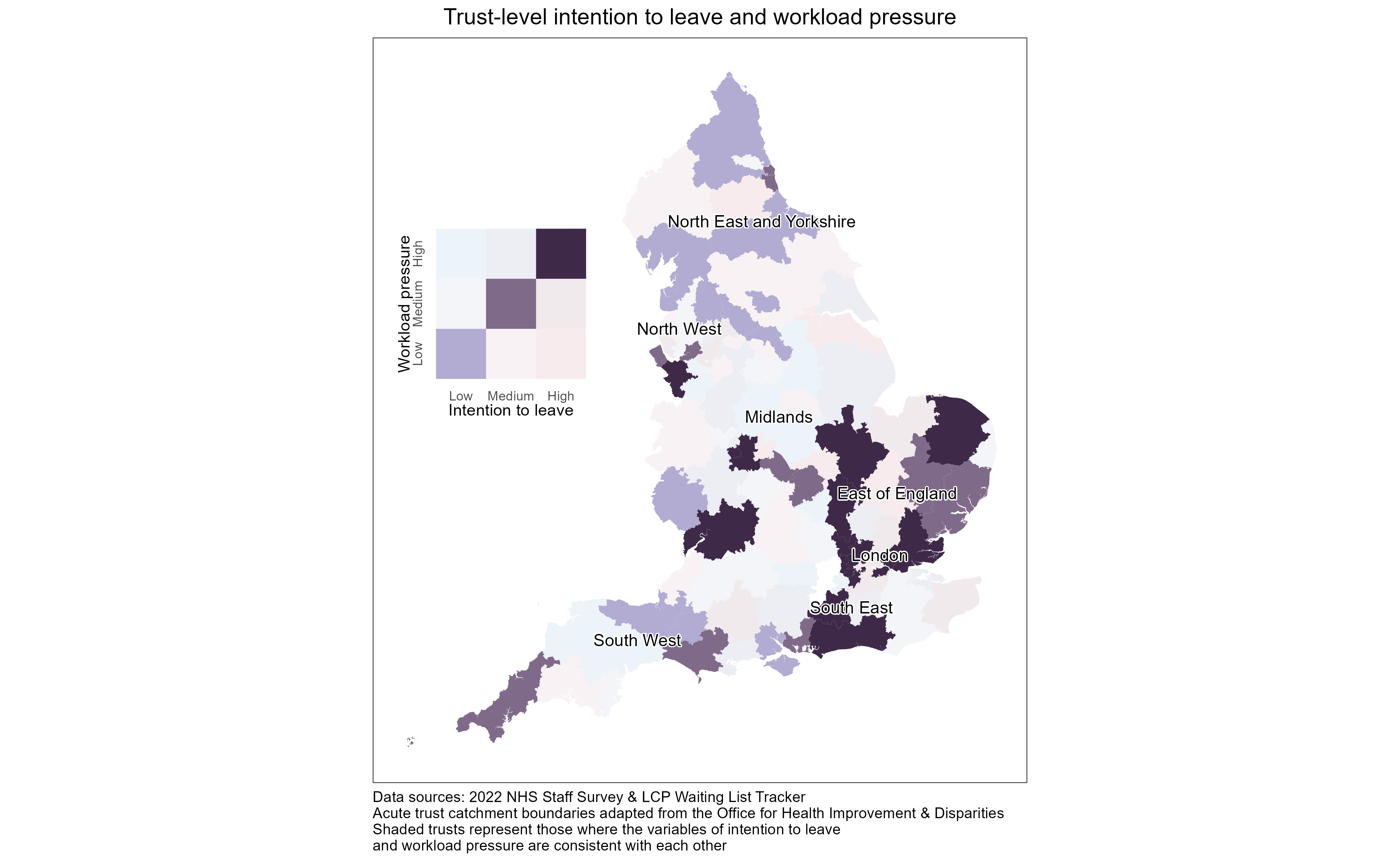

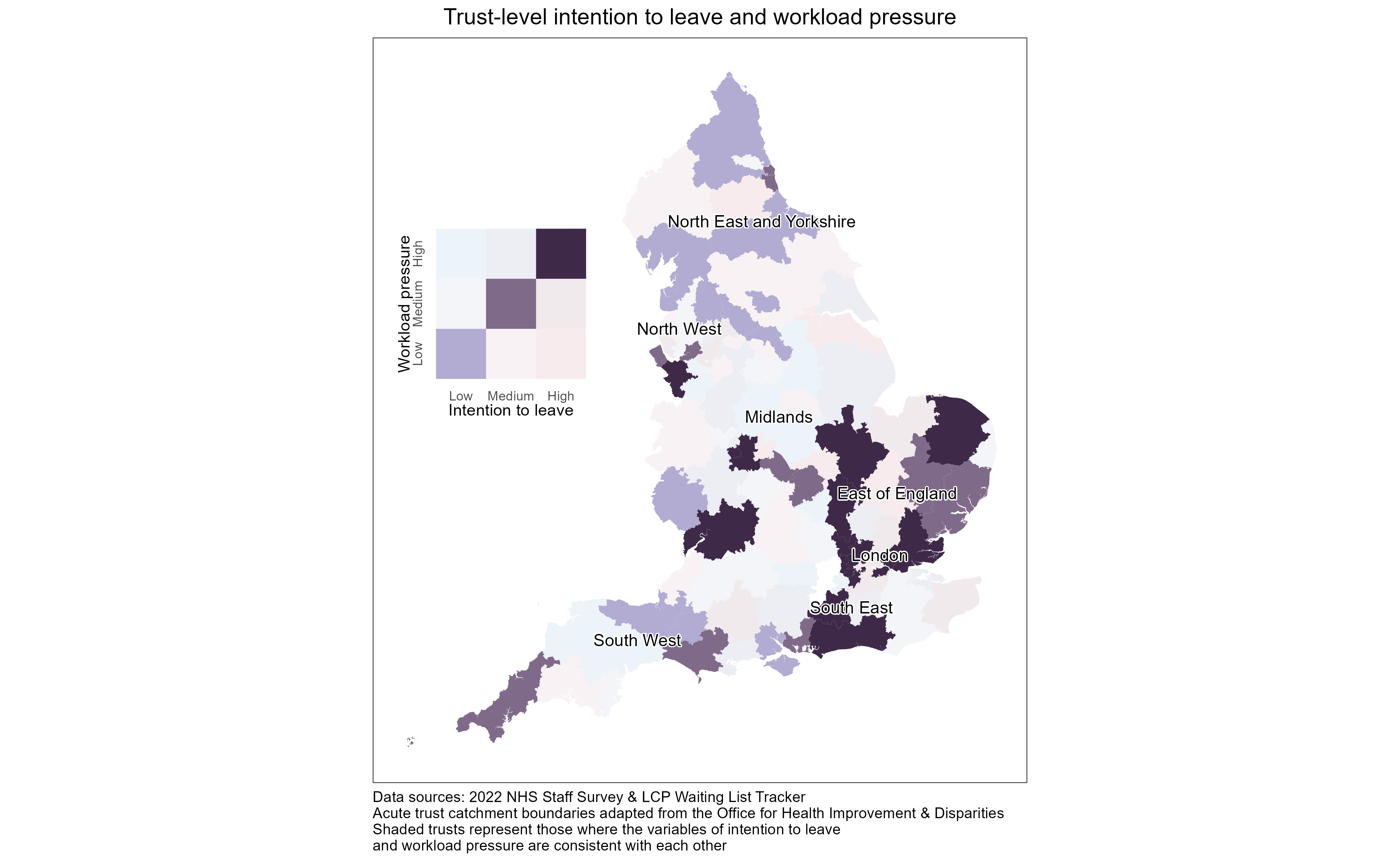

Our visualisation of the data reveals substantial geographical variability in staff intention to leave. We found that 83% of trusts in the top quintile of intention to leave are located in London and the East of England, while 52% of trusts in the bottom quintile of intention to leave are located in the North West and North East and Yorkshire. Understanding the factors driving this variation and encouraging better performing trusts to share best practice could be a proposal within the Government’s new workforce plan.

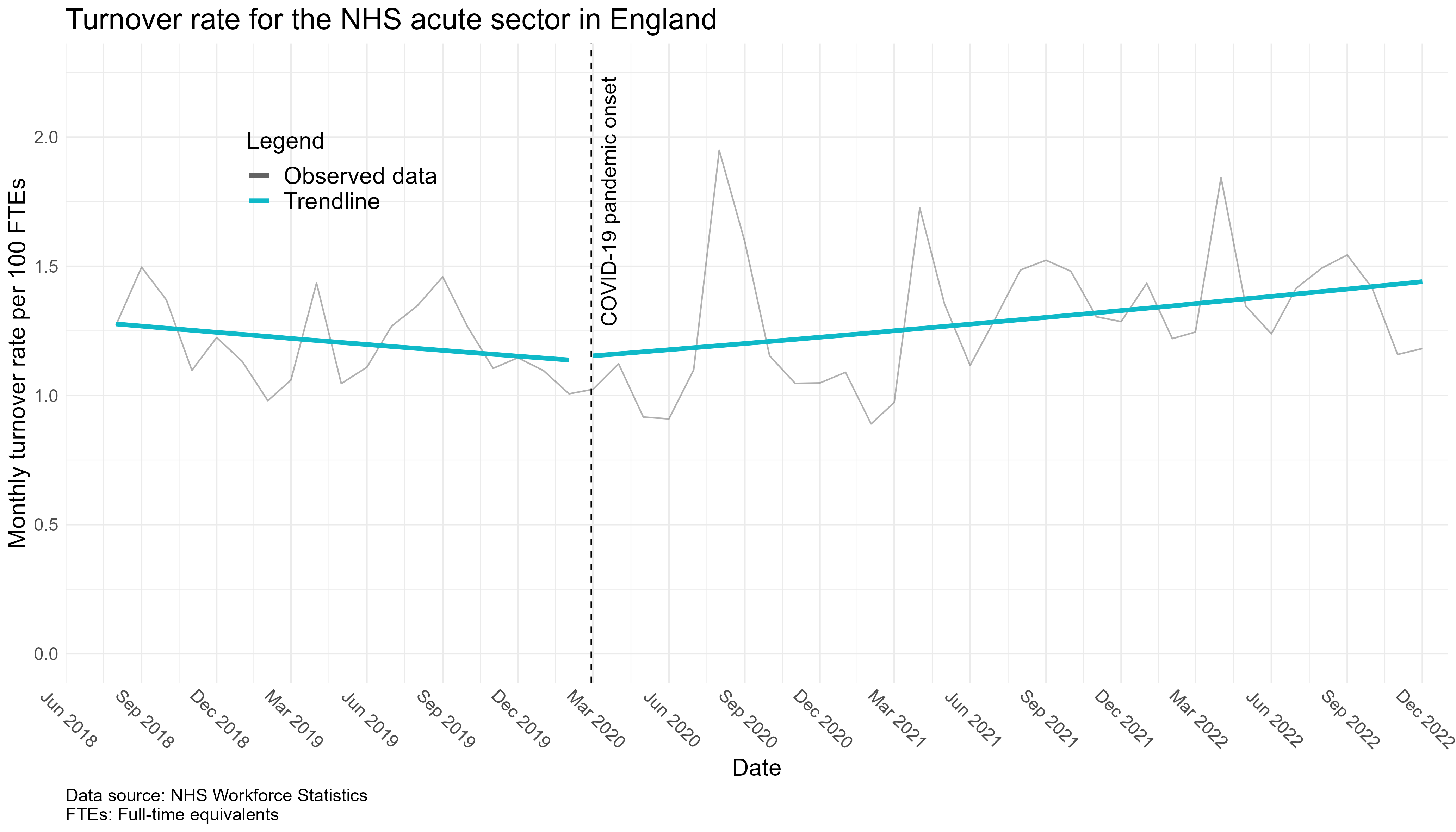

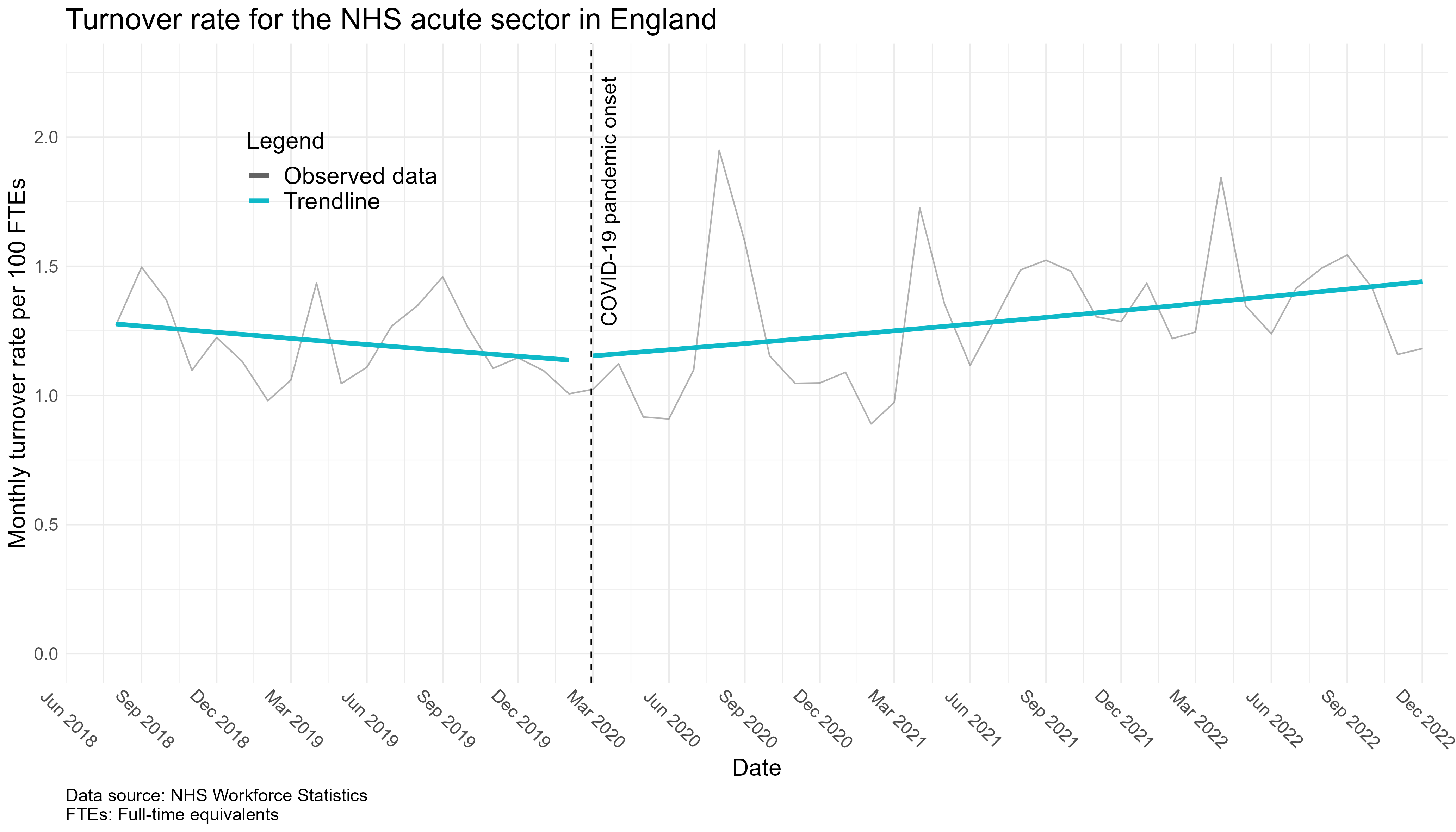

In addition to employee satisfaction and intention to leave, actual turnover rates are an important marker of organisational health. From mid-2018 to early 2020, the monthly national staff turnover rate for the acute sector in England was declining. However, several months into the Covid-19 pandemic, the turnover rate spiked and has been on an upward trajectory ever since, similar to staff intention to leave which climbed from 19.6% in 2020 to 23.8% in 2022. While further analysis is needed to link employee intention to leave with actual turnover rates, the data suggest that the organisational health of the NHS acute sector – as measured by staff satisfaction levels and turnover rates – has deteriorated since the pandemic.

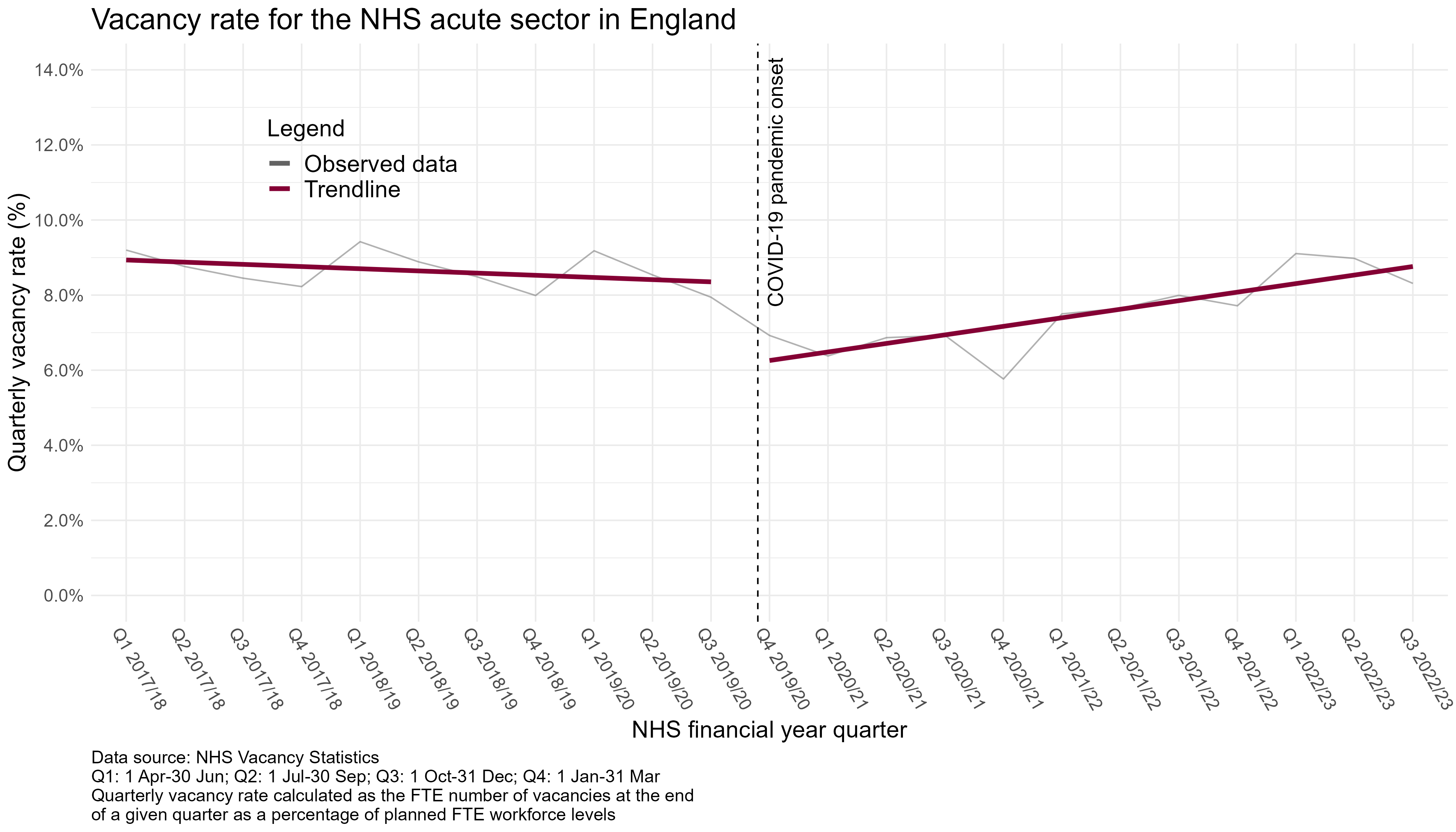

Looking at staff shortages or vacancies may help us understand whether staff are leaving the NHS entirely or whether turnover reflects movement within the system. The NHS reports the staff vacancy rate for each financial year quarter by dividing the FTE number of advertised vacancies by planned workforce levels and converting this to a percentage. Prior to the pandemic, the national vacancy rate for the acute sector was gradually falling, similar to the national turnover rate. Unlike the turnover rate, however, the vacancy rate experienced a marked drop during the pandemic’s onset.

This drop is likely an artefact of disruptions to staff recruitment efforts during the pandemic as opposed to a true fall in staff shortages, a hypothesis supported by the four-year high in agency spend recorded for 2020-2021. Since its drop, the national vacancy rate has been, on average, increasing, although it is unclear if this increase represents simply a return to pre-Covid levels or a more concerning acceleration in vacancy rates that will continue into the future.

A commonly cited driver of employee turnover, especially since the advent of the pandemic, has been burnout due to heavy workloads and inadequate staffing. However, our research suggests the picture may be more multifaceted. To investigate the relationship between turnover intention and workload pressure, we derived a measure of workload pressure for each trust based on the size of its elective care waitlist relative to the number of FTE staff. Then, we visualised trust-level values for workload pressure and turnover intention on the same map, shading in trusts where the two variables were consistent with each other. This revealed some evidence of a relationship between staff turnover intention and workload pressure. Trusts affected by both high workload pressure and high intention to leave include many in London, a number in the East of England, and a smattering throughout the rest of the country.

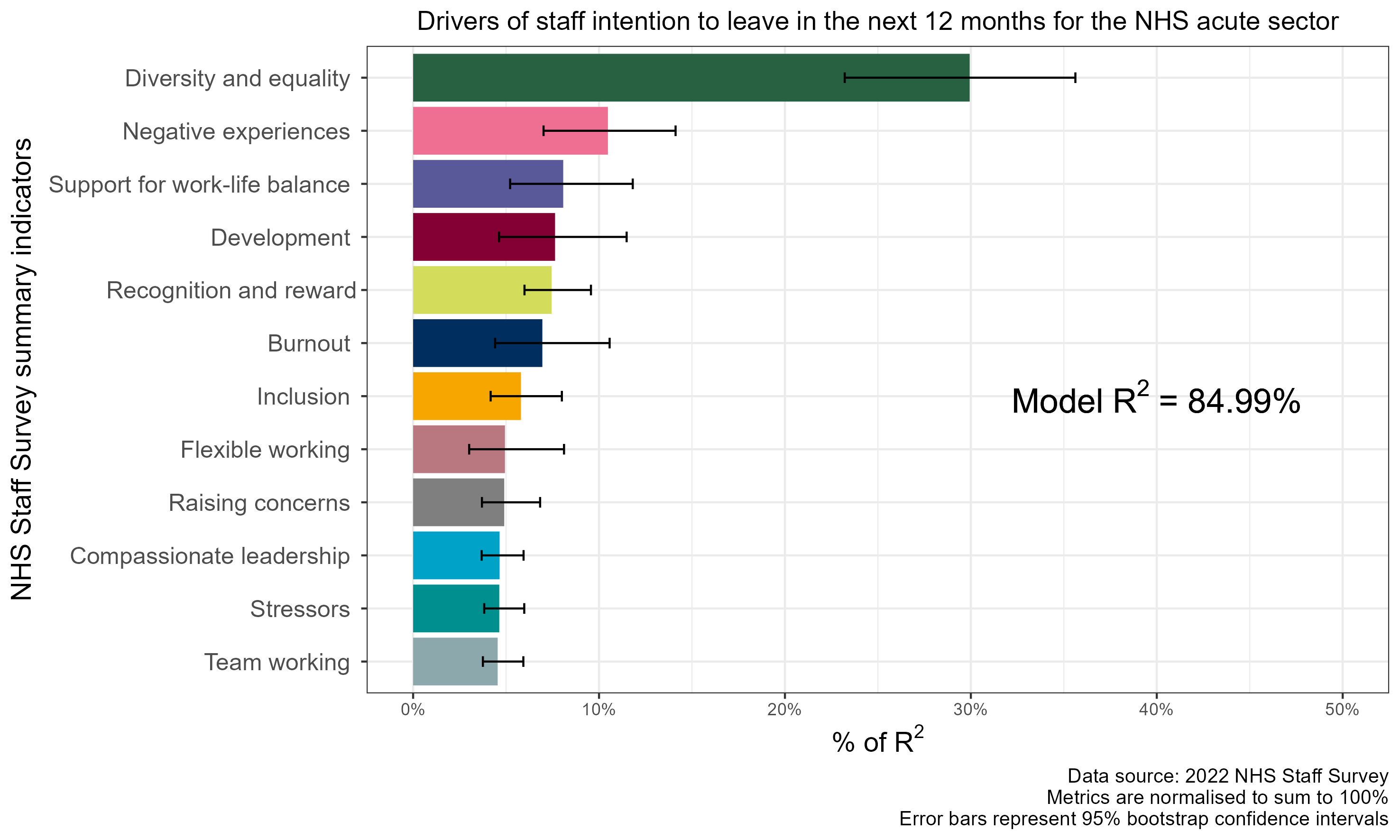

While some areas of high correlation were identified, it is clear that there are other factors influencing staff intention to leave. Using relative importance analysis, we identified Diversity and Equality as the most influential factor in contributing to staff intention to leave among the 12 Staff Survey summary indicators examined. This finding is especially notable in light of reports documenting a pattern of racism and discrimination in the NHS. While tackling burnout is clearly vital for retaining NHS staff, building a positive, inclusive work culture is perhaps even more important.

In conclusion, our analysis reveals a stark picture of lower satisfaction levels and higher staff turnover rates currently facing the NHS acute sector. Understanding the drivers is key to the success of the Government’s new Workforce Plan. Although further research is needed to untangle the complex web of workload demands, staff satisfaction, and staff retention, next steps for improving the NHS’s organisational health could include addressing disparities in staff satisfaction levels between trusts and investing in diversity and equality efforts to foster inclusive workplace environments. By understanding the root cause of NHS workforce challenges and designing solutions to properly address these, we can improve not only workforce satisfaction in the NHS but also patient satisfaction and outcomes.