How policy can help stimulate EM growth and unleash global growth: a macro-demographic view

This content is AI generated, click here to find out more about Transpose™.

For terms of use click here.

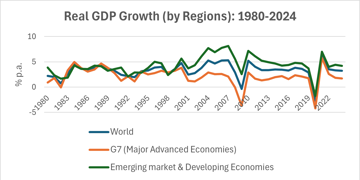

Emerging markets (EM) growth, the largest component of global economic growth, has been very weak and sluggish over the last two decades. Additionally, the global economy has been facing several complex uncertainties and headwinds since the start of this decade. Most countries are on a downward growth trajectory compared to the pre-covid years. Growth has been very much a'wanting for the majority of countries.

In this blog, I look at the crucial role that EM growth plays in the global economy and how this can be unleashed through policy changes. Currently, sluggish and weak EM growth is dragging down the global economic growth – but I believe it is possible to achieve the higher 1990s EM growth levels through policy changes. Unlike recent reports and papers focused on fertility rates and growth where the effects are likely to show up couple of decades later, my focus is on how we can achieve higher EM and global growth over the next 5 or 10 years. I view economic growth from a macro-demographic lens. I highlight necessary policy changes to generate more active and productive workers, who utilise their working hours more effectively.

Why should investors care about demographics?

Because GDP growth and GDP per capita growth, as well as inflation, r*, yield curve and equity premium that define the investment environment, are fundamentally affected by demographics not just in the long-term but in the immediate, short-term and medium-term.

My perspective on demographics develops Peter Drucker’s view and considers “people characteristics” i.e. people as workers and consumers as the etymological core of demographics. Demographics is not just about age only. Two people who are of the same age are not identical or very similar in their consumer and worker behaviour, and neither are the most ageing countries’ with respect to consumers and workers1. Age and numbers of people do not fully describe the demographics of any unit be it the family, city population, state population or country population. The characteristics of any individual as a consumer (over lifetime, birth to death) and as a worker (over the working life) contribute to the overall GDP and thereby GDP growth of a nation or a region. Demographics affect the investment and wellbeing of every household, company and country in the world, across both EM and DM (developed markets) countries.

Generating growth in the face of the ongoing rapid demographic transition (big changes in consumer and worker behaviour) requires changes in policies affecting not just labour markets but also pensions, health, education, lifelong training, taxes and benefits, immigration and most of all technology and trade in an increasingly globalised world. I have been publicly advocating these changes to counteract transformations in the structure of the labour force and longevity2. While my focus is on emerging markets and developing countries, growth challenges are a priority across the developed world too.

In the chart below, the GDP growth differential between EM countries (versus the DM countries) was nearly as high as 6%. The EM growth slowdown accentuated from 2006 pre GFC to the pre-Covid 2019/2020 period. While rapid EM growth led to high global growth in the 1980s and 1990s and still contributes the lion’s share of Global GDP growth, it is still declining. This blog is about how to reverse this decline.

What factors contribute to GDP growth?

I use a national income accounting framework3 that constructs a labour-based decomposition of growth. This macro framework is easily understandable as three labour based components aggregate to yield GDP growth and changes in those components lead to changes in GDP growth. The three components that explain GDP growth are:

- working age population growth reflects the changing potential labour force

- labour productivity growth explains productivity changes due to technology adoption, efficiency gains and learning by doing over time

- labour utilisation growth derived from, and very closely related to, growth in total hours worked reflects how effectively utilised are hours worked

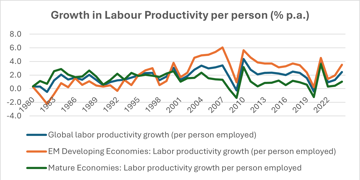

I present charts below that highlight each of the three GDP growth components. The largest contributor to EM growth in recent decades has been labour productivity growth, but sadly it has been on a downtrend. It has been adversely affected by the pandemic through its inimical effects on informal EM labour markets. I believe that the post-Covid recovery in EM labour markets is incomplete. Informal labour markets are typically not conditioned to recover from global shocks like a pandemic but policy responses have not addressed this and have been slow in stimulating the labour markets.

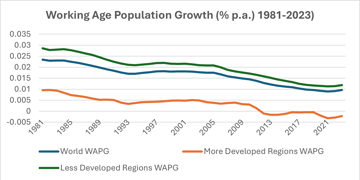

The first chart below shows the downtrend in working age population growth. This illustrates the broader trend of declining population growth across nearly every country in the world due to lower fertility rates. Additionally, interest rate policies, trade dislocations due to supply chains, post pandemic labour market slow recoveries have also weighed down on the jobs and employment conditions in emerging markets economies.

The second chart below illustrates that labour productivity growth for EM countries (in orange) is higher than that for the advanced countries and the whole world but has been on a downtrend post the Global Financial Crisis and is the major driver of GDP growth.

So, what’s the answer? My advice to advanced countries which have seen a drop in labour productivity growth over the last 15 years, is to increase female labour force participation and supplement it with increases in youth employment.

How to unlock barriers to getting women actively and productively employed?

Recently at a large global conference, we discussed the gender inequality across the NEET (Not in Employment, Education & Training) category of workers noting that women form a much higher proportion of NEET. Women face barriers to equal participation and opportunities in employment, education and training starting from 15 years of age. The barriers to full equality in labour markets, education and training remain impediments to labour productivity growth and GDP growth.

Female workers and young workers contribute with higher labour productivity growth than the average male worker, as they typically start on average with lower labour productivity levels. Flexible work conditions with the use of technology, better childcare facilities, training and lifelong education while accepting the norms of the biological life cycle of women (childbearing, menopause etc) are a must for progressive policy makers in emerging markets economies. Training to allow both young and female workers to use technology efficiently in their roles would untap future productivity potential and growth.

Another challenge in EM countries is job creation for the newly educated youth and inability to create jobs leads to dissatisfaction, unrest and even violence as the Arab spring and recent unrests in many EM countries have shown. With youthful exuberance, updated knowledge and fresh skills, this is a resource pool that needs more effective deployment to yield growth.

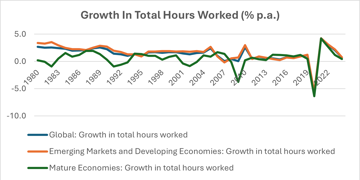

The third chart shows growth in working hours and is dependent on increasing the hours worked. In the poorest of EM economies, younger workers and women contribute informally towards supporting their families, farms and enterprises alongside the main breadwinner who is typically the male head of family.

The use of technology to allow women to better balance family life with work life was the policy advice I gave to advanced countries dealing with the ageing time bomb and facing shortage of domestic workers, twenty-five years ago. Women live longer than men, are better educated in terms of college graduate numbers in the G20 countries and also in some progressive emerging countries. If country leaders and policy-makers care about future growth of GDP and increased wealth of their citizens, then tackling gender inequality in labour force is a policy change imperative and long overdue. The same arguments hold across both developed and emerging markets.

Immigration to plug the skills gap is a partial solution to increasing working age population and labour productivity growth but EM countries have experienced emigration with their skilled workers leaving for better rewards overseas. The EM countries should work hard to reverse the so called “talent drain” through attractive policies to prevent their skilled citizens from migrating abroad and contributing to GDP growth of other countries. Selective immigration by developed countries as per their own needs was a policy advocated in the Demographic Manifesto (2000).

In addition to the above-mentioned labour policy changes, the use of technology such as digital access, Big Data, AI, Machine learning and Web 3.0 can allow for a reduction in the productivity gap between the haves and the have-nots. Technology and Education are a big part of the new globalisation paradigm, and their spread is already showing promising effects in the poorest countries of the world.

Better infrastructure, health, technology and financial access are all necessary to complement the labour policy changes — policy changes need to be structural and holistic in their determination and deployment. Policy makers need to embrace flexible e-nabled retirement, gender equality at work and selected immigration as part of the holistic transformation of labour markets. It is clear that demographics play a key role in driving growth and that attention needs to be given to developing policy frameworks that cater to the societal changes we are seeing.

I will be examining some of these drivers in future blogs, focusing on Immigration, AI and the work force as well as labour force participation changes across generations, all of which affect the micro and macro labour contributions to growth.

1 In previous research more than a decade ago I demonstrated that the 5 oldest countries are very different in terms of Fiscal Burdens in terms of ageing and micro conditions of their consumers and workers.

2ADB Institute Working Paper based on the 2011ADBI Tokyo conference keynote speech on longevity lessons for Asia from the West.

3 Demographics Unravelled (2022, Wiley Finance) discusses these issues and includes underlying references.

Subscribe to our thinking

Get relevant insights, leading perspectives and event invitations delivered right to your inbox.

Get started to select your preferences.