Whither deglobalisation? Migration, mobility and megacities

This content is AI generated, click here to find out more about Transpose™.

For terms of use click here.

Despite political narratives around deglobalisation and immigration restrictions, data reveals rising global migration, mobility and urbanisation. This blog focuses on people movement - challenging the idea of a deglobalisation trend.

We are currently in unprecedented times in geopolitics as well as in local and regional politics. Over the last few years, especially since the pandemic began, there has been strong momentum in the use of the term deglobalisation. This coincides with headwinds and right-wing sentiment towards immigration in the richer host nations of the world. If one were to go by simple news headlines, one might end up concluding that migration numbers were decreasing and that iron walls as well as migration rules heavily constrain the open flows of migration.

This blog provides data-based analysis on the connected themes of migration, mobility and megacities which question the popular “deglobalisation hypothesis” and has implications for economic growth and investments. Aside from increased people flows over last few years there has been a rapid increase in global flows of investment, information, data and education. This blog focuses on movement of people.

A summary of the key points and investment insights from this blog are as follows:

- Migration across countries is a politically sensitive issue with economic implications through productivity, growth, incomes, remittances and family welfare. Current political regimes have seen an immigration pushback across many rich countries with increased protectionism and right-wing ideology growth.

- Immigration has implications for GDP growth, living standards, integration of diverse different populations as well as social welfare. GDP growth, living standards and worker skills influence investment returns and asset allocation.

- Immigration has gender inequality and climate implications which need counteracting to avoid worsening of the current state. International mobility too has surged due to cheaper air travel, travel insurance and phone calls. But this increase has not been equal for men and women, disadvantaging women in jobs and financial access.

- Future intra-country and inter-country travel will be governed by climate change and environmental considerations with implications for international skills gaps, incomes, capital flows and investments as well as exchange rates on a fundamental basis.

- Megacities are a growing cause for attention and concern in emerging markets due to shortages of infrastructure, affordable housing, clean air, clean water and the emergence of slums. These are coincident in many cities with crime, lower longevity and poorer quality of life as well as later life morbidity. The health implications are already very severe with Air Quality indices the most monitored index in those cities.

Migration: a sensitive and volatile issue.

Given the recent press in the buildup to the vast number of national elections in 2024, a common plank of the debated manifestos was “immigration policy” in the richer host countries, even amongst the so called liberal rich countries. My personal view is that lot of it is driven by the lower growth in GDP per capita or living standards compared to the 1980s and 1990s. A common takeaway from popular press is that immigration is under threat in the wake of right-wing sentiment and protectionist moves. Is that right? Not so, says the international migration data from the OECD Migration Report 2024. It shows that advanced OECD countries saw a record 6.5 mn new permanent-type immigrants in 2023 with most of the increase from the family migration category (+16%) and humanitarian migration (+20%), beating the 6+ mn numbers from 2022. Temporary labour migration to OECD countries also continued growing in 2023 after an unprecedented increase in 2022. More than 2.4 mn work permits and authorisations were granted in OECD countries (excluding Poland, 28% above pre covid levels and 16% increase over 2022). International student flows also increased by 6.7%to reach 2.1 mn new permits. The number of new asylum seekers in 2023 also broke OECD migration records with 2.7 mn new applications 30% higher than 2022.

A look back over nearly 5 decades reveals that while net number of migrants have increased in all G6 countries, they have played a more important role offsetting the negative natural change (births minus deaths) in Germany, Italy and Japan, 3 of the oldest 5 countries in the world.

The migration numbers for France, Germany, Italy, Japan, UK and US contradict any hypothesis of globalisation reversal. In contrast to the rich advanced G6 countries, the EMG6 countries lose talent and human capital to the richer countries via emigration. The highlights of the migrant population composition using latest OECD migration data show:

- 17% of the self-employed in OECD countries were migrants (up from 6% in 2006).

- Migrant entrepreneurship added 4 mn jobs (2011-2021) across 25 OECD countries.

- Contrasted with the native-born, migrants are more likely to be: own account holders, in false self-employment and gig economy participants.

- 150+ mn people in OECD countries were foreign born (sum of Germany and Italy in population terms, larger than Japan), with US host to nearly 50 mn and its foreign born population share increasing from 9% to 11% (2013-23)

- Temporary labour migrants also increased-seasonal migrants increasing by 5% and working vacationers by 23% while inter-company transferees decreased by 11%.

- For the first time, number of asylum seekers in the US (> 1mn) surpassed those of European OECD countries taken together.

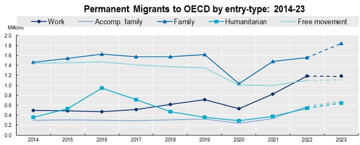

The chart illustrates uptrends in permanent types of immigration over 2014-23 to the OECD.

Temporary foreign workers for US, Australia and Japan increased and so did asylum seekers mainly from the top 5 host countries Venezuela, Colombia, Syria, Afghanistan and Haiti.

Refugees and employment of immigrants

For 2023, Germany topped the new refugees hosting league table (140K) followed by the US, Canada and UK (65K). Women migration flows differed by women migrating for family reasons whilst men did so for professional reasons. Immigrants displayed higher employment rates than the native born by 1%.

The employment rate of migrants in OECD countries increased from 71.4% to 71.8% (2022-23), with 22 out of 35 OECD countries (data available both 2022 & 2023) surpassing the 2022 levels. Immigrant unemployment continued to decrease, reaching an average of 7.3% across the OECD in 2023 (0.3% lower than 2022). The increase in the immigrant employment rate was particularly high in some European countries, such as Slovenia (+2.8 %) and Sweden (+2.4 %) with native-born employment rate falling slightly (-1.2 and -0.4 %). In previous research covering four centuries of immigration, I highlighted differences across the largest European countries in terms of their immigration policies and practices. The immigration policies in many OECD countries have taken a stricter approach in the wake of lower economic growth, greater market volatility, supply chain restrictions, geopolitics and increased regionalisation. Tighter asylum legislation in response to high demands on infrastructure to ease pressure on housing and public services, is common across most countries.

The interest of most working migrants is to get gainful employment and get paid fairly as they work, get integrated into the relevant workplaces and industries. But gender, age, education are factors that influence the employability and tenure of the migrant worker. The chart below highlights the employment changes of migrants relative to the native workers.

In a previous document, LCP Vista magazine, I shed light on why migrants matter for the growth numbers in ageing countries through their numbers in the work force, their productivity and the hours worked using a National Income Accounting macro framework. There exist significant differences between migrants and native-born workers within the OECD in terms of education and poverty. Immigrants are however aware of these differences as well as the benefits, costs, challenges, legality etc of going to a rich host country from their native country.

Mobility: how mobile are migrants?

Highlights of mobility using mid-2024 data are below:

- 304mn international migrants at mid 2024, of whom 168 mn were labour migrants

- 48% migrants were female

- 13% migrants were children

- 11% migrants were between 15-24 years old

- Remittances were USD 857 billion

- Over 2014-2025, 72000 migrants were recorded as missing or dead

- 207K migrants were human trafficking victims between 2002-2022.

- 44mn refugees and asylum seekers in the world

- 86mn people internally displaced

- 59K refugees were resettled.

Women and migration

The UN DESA and Global Migration Data Portals indicate that the share of female migrants has not changed significantly in the past 60 years. However, more female migrants are migrating independently for work, education and as heads of households. Despite these improvements, female migrants still face greater discrimination, are more vulnerable to mistreatment, and can experience double discrimination as both migrants and as females in their host country in comparison to male migrants. Lower incomes and unequal incomes for women as part of gender inequality impede their access to mobility internationally. Mobility like Financial Access has been gender unequal. Female immigration patterns display relative differences across regions too. Women’s Mobility is still restricted in most regions of the world. Middle East and North Africa trail sub-Saharan Africa but are making ground from a much lower base.

Natural disasters and displacement

Below are some statistics to set the scene on internally displaced people is helpful for context.

- Of total of 46.9 mn new internal displacements registered in 2023, 56% were triggered by disasters. Disaster-induced displacements include both weather-related hazards (storms, floods etc) and geophysical hazards (earthquakes, volcanoes, tsunamis)

- As of 31 December 2023, at least 7.7 mn people in 82 countries and territories were living in internal displacement because of disasters that happened not only in 2023, but also in previous years This represents 11% decrease in the total number of internally displaced persons due to disasters compared to 2022

There were major regional differences across the share of women among total migrant workers. In 2019, women represented more than 50 per cent of all migrant workers in Northern, Southern and Western Europe but the share was below 20 per cent in the Arab States as per the ILO in 2021.

Although the labour force participation of migrant women was lower than that of migrant men, the labour force participation rate of migrant women was higher than that of non-migrant women in many countries.

Climate change and mobility

Highlights comparing 2023 vs. 2022.

- 56% of 47 mn new internal displacements were triggered by disasters

- 8 mn people living in internal displacement (IDPs) as a result of disaster

- 11% decrease in total number of IDPs in 2023 vs 2022

There was an increase from 2019-23 in internal displacements but this may be due to the lingering effects of Covid displacements. The importance of climate change as a major global and systemic risk component also lends itself to look at the impact on internal migration due to climate change. Projections by the Institute of Migration GMDAC indicate internal migrants in millions by 2050, with the total of nearly 216 mn displaced. This is what Al Gore warned about in presentations to the Middle-East countries.

Megacities

The UN’s World Urbanisation prospects 2018 highlighted the fast growth of megacities (cities with populations greater than 10 million) and the fact that most of these are and would be in the future too in emerging markets. Many of these cities with very high population densities create negative external effects of air pollution, water pollution, poor soil conditions, congestion and crime. The continued internal migration from rural to urban areas creates issues of health, sanitation, inequality placing strains on existing infrastructures which cannot be modernised or replaced easily. These extend beyond residential real estate and commercial real estate to datacentres, storage etc. In the absence of external migration, internal migration towards large connected cities allows migrants from smaller villages and towns to benefit economically, socially and intergenerationally too. The chart below lists the cities with highest population density in 2020 and projections until 2030

Smaller countries typically have higher population density on average but they also have higher GDP per capita, better education and easier governance.

SDG1 Goal of No Poverty speaks to the slums in the urban areas; many such slums are located in larger EM cities with lower GDP per capita in Africa, Asia and the Middle East.

Conclusion

The 3Ms, migration, mobility and megacities, do raise questions vis-a-vis the “deglobalisation hypothesis” but more importantly they have effects on growth, real estate & infrastructure, sustainability & climate change, productivity and most importantly gender equality the critical policy imperative to raise growth. Residential real estate and infrastructure as asset classes are most impacted by the 3Ms.

Subscribe to our thinking

Get relevant insights, leading perspectives and event invitations delivered right to your inbox.

Get started to select your preferences.